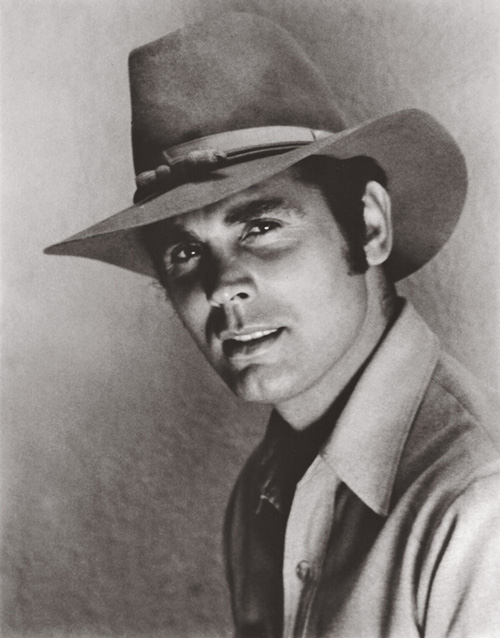

An interview with big- and small-screen star Michael Dante

By JOHNNY D. BOGGS 5/12/2023

Michael Dante, 91, appeared in nearly 200 big- and small-screen productions. Western film buffs would recall him best from such movies as Westbound (1959), with Randolph Scott; Apache Rifles (1964) and Arizona Raiders (1965), both with Audie Murphy; and as the title Blackfoot chief in Winterhawk (1975). Born Ralph Vitti (Dante picked his professional name after signing with Warner Bros.) in Stamford, Conn., in 1931, he started acting in fourth grade and majored in drama at the University of Miami. Before moving to Hollywood, he played professional baseball in the Boston Braves and Washington Senators organizations. Nursing a shoulder injury, he took a screen test arranged by big band legend Tommy Dorsey and left pro ball. From 1994–2008 he hosted the radio series The Michael Dante Classic Celebrity Talk Show, out of Palm Beach, Calif. Dante has since turned to writing both nonfiction and fiction, including the autobiography Michael Dante: From Hollywood to Michael Dante Way (2013); My Classic Radio Interviews With the Stars: Vol. 1 (2021), co-authored by wife Mary Jane Dante; and such novels and novellas as the post–Civil War Six Rode Home (2018); the Western sequel Winterhawk’s Land (2017) and the redemption tale Macabe’s Journey (2022), all from BearManor Media. Dante [michaeldanteway.com] recently took time to speak with Wild West about his various careers.

WHAT REAL-LIFE WESTERNER WOULD YOU MOST LIKE TO HAVE PLAYED ON-SCREEN?

Jesse James. He was a colorful character, very deceptive and knew the territory and despised the railroad. I wanted to make him a colorful character. He was a great horseman, and he and his brother were a team, and his gang was a family. He began to get a little too aggressive, which led to his demise. I made notes about his character, but I never got a chance to play him.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO PLAY CRAZY HORSE ON THE 1967 TV SERIES CUSTER?

I had read a great deal about him and had tremendous respect and love for native Americans. He was my favorite because he was a visionary and a militarist, a deep thinker, had a high element of a spiritual side. That was the kind of man I am. I could make a wonderful marriage to this character and do something exciting and interesting and show to the American audience what kind of man and leader he was.

But [producer David Weisbart] passed away after the seventh show, died of a heart attack on the golf course, and we were knocked off the air because of political correctness. Custer became a very bad name, unfortunately, so we were off after 17 shows. So I never really got a chance to share with the audience what I eventually was going to contribute to the character and the story.

WHAT ARE SOME FAVORITE MEMORIES FROM YOUR DAYS PLAYING PRO BASEBALL?

I was underage but signed to a pro contract with a $6,000 bonus. When I received that bonus, the first thing

I did was buy our family a brand-new four-door Buick—whitewall tires, radio and heater. It was a beautiful sedan.

Number two was, without a doubt, putting on the major league uniform. The Washington Senators invited me to spring training in 1955 in Orlando, Fla., and the first moment I put on the uniform, I sat by my locker, turned my back on everyone and just shed tears.

WHO WAS YOUR FAVORITE BALLPLAYER AND WHAT MOVIES DID YOU LIKE AS A BOY?

Joe DiMaggio. The Westerns.

We loved Westerns and the Dead-End Kids. We didn’t have any money, but theaters had exit doors. After the first running of the movie and the serials, they would open the side doors. Everybody would exit out of the side instead of going out the front. We used to sneak in!

If we had a nickel, we’d buy a Baby Ruth or a Mounds, and that would be lunch or early dinner, because we’d stay and watch two shows. I had a great love for Buck Jones, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Ken Maynard, John Wayne and all the great stars that did Westerns in those days. We’d sit there and idolize all of them and wanted to be just like them.

When we played cowboys and Indians, I was the only one who’d play the Indian. We drilled a hole in the top of a broomstick and pulled a string through like reins, put a pad in the middle of the broomstick, and that would be our horse. And we’d chase with a cap gun. “Bang, bang! you’re dead. I got you.” That was the beginning of my love of sports, my love of movies and my love of Westerns.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE WORKING WITH DIRECTORS BUDD BOETTICHER AND SAM FULLER?

The best. Budd Boetticher gave me my first opportunity to star in a motion picture, and that was Westbound. I was under contract to Warner Bros., making $275 a week, which was fine.

I told Budd I had an idea about my character [a one-armed Army veteran] using a Winchester. I picked up the script and went to props and took home the Winchester. Over the weekend I learned to crank it with one hand. It wasn’t written [in the script]. When I showed Monday, Budd said that was beautiful. That was my contribution.

In first scene that day Randolph Scott was to teach me you can do a lot of things with one hand and one arm. So, in the story he had to teach me how to crank that Winchester. Unfortunately—and with all due respect, as he was a wonderful man and actor—he was not as coordinated as I was. He couldn’t do it. I took all day long—36 takes! At that point Scott’s hands were bleeding. They put tape on them, kept doing it, and he kept fumbling. Finally, he got it.

Budd was a great storyteller. He had a knack of telling stories on the set to keep everybody entertained. He had a great sense of humor.

Sammy Fuller was another wonderful director to work with. We did the provocative Naked Kiss [1964 neo-noir]. He was so innovative. Every day he had something new. One morning Sammy came in at 7 and said, “Michael, I’ve got something today that you’re gonna love. You’re going to shoot your own close-up.” He put a 2-by-6 on the dolly below the lens, and I pressed my shoulders up against that 2-by-6. You can’t go left, you can’t go right—you have to stay perfectly still while your shoulders are slowly pushing that camera on the dolly. Normally I don’t go to see rushes, but I saw the close-up and couldn’t believe how perfect it was. I filled the whole screen. And I did it—I filmed my own close-up.

HOW WAS IT TO CO-STAR IN WESTERNS WITH AUDIE MURPHY AND RANDOLPH SCOTT?

When I was sitting in the Strand and Palace theaters [as a teen] in Stamford, Conn., they ran newsreels, and one day there was Audie Murphy receiving the Medal of Honor. We were tough kids, good athletes, great competitors, and here he was, our No. 1 hero, and he was not much older than we were. To think one day I’d be co-starring in Apache Rifles and Arizona Raiders with Audie Murphy, whom I idolized off- and on-screen. A lot of people don’t know he wrote poetry and lyrics. He had a great sense of humor, always on time, always knew his dialogue.

Randolph Scott was a perfect gentleman and a great businessman. He was also a great horseman. He could come in cantering and just slip off the horse and be in stride and tie the reins to the post in one motion.

HOW GOOD A HORSEMAN DID YOU BECOME?

I was very good. I learned to ride when I was growing up. There was a buddy of mine, our best pitcher, but he liked to ride horses. He worked at the stable. He was currying a horse and doing his duties with hay and manure in the corrals. “I’ll teach you how to ride,” he said. “It’s a lot of fun, but you’ll have to clean the stalls, wipe down the horse when you’re done.” The owners liked me as I progressed, and I got to be pretty good. It’s like riding a bike—you don’t forget. So I was able to take that with me when I worked on my first Western in Hollywood. I got better as I got along.

YOU PASSED UP A CHANCE TO CO-STAR IN TV’S THE UNTOUCHABLES. WHY?

I was to be the star in 13 episodes, and Robert Stack was to be the star in 13 episodes. We’d alternate.

Producer Quinn Martin offered me everything. I said I want to do films, signed a contract [with 20th Century Fox] and did Seven Thieves[with Edward G. Robinson and Rod Steiger]. Unfortunately, [Fox] was bankrupt and couldn’t distribute the picture when finished. It had one picture doing well in New York called Journey to the Center of the Earth, so it put the money into distribution of that film and didn’t have money for Seven Thieves. Ours was an art piece. It was commercial exploitation.

I’d turned down several series. As a matter of fact, I turned down The High Chaparral [1967–71]. After I guest-starred in a Bonanza episode called “The Brass Box,” executive producer David Dortort said, “I’d like you to do a series for me.”

“OK, what do you have in mind?”

“We’re doing a series called High Chaparral. Cameron Mitchell is starring in it, and I want you to play Manolito. He’s Hispanic.”

“David,” I said, “I don’t want to pigeonhole my career being a Latin actor because I played Ortega in ‘The Brass Box.’…I just don’t want to typecast myself.” [Henry Darrow landed the Manolito role.]

HOW DID THE MICHAEL DANTE CLASSIC CELEBRITY TALK SHOW COME ABOUT?

After filming Winterhawk and The Farmer [1977], I was doing some publicity in Palm Springs, Calif. I did a radio show (KXJ at the time), and the interviewer said, “Would you be interested in doing a radio show?”

“I don’t know anything about radio.”

“I’ll teach you,” he said.

He signed me to a contract for 13 shows. The first couple of shows I was terrible. I went overtime on the commercial. I got in or out too late. But I began to learn what I was doing. At the end of 13 shows he said, “I want to sign you to 13 more.”

“What I’ll do,” I said, “is pay you for the airtime, and I’ll get sponsors for my own show.”

“Wow, you learn fast,” he said.

That was the beginning. That went on for 12 years, and I eventually moved to Palm Springs. Mary Jane became my radio operator and sound editor, and we were a dream team. We had hour-long interviews with all these people.

We didn’t make any money when we did the shows, but we paid our bills.